floverfelt.org

Thoughts, notes, etc.

Chapter 1: Libo

by Florian

I’ve wanted to do this for a while: A complete analysis of Speaker for the Dead by Orson Scott Card.

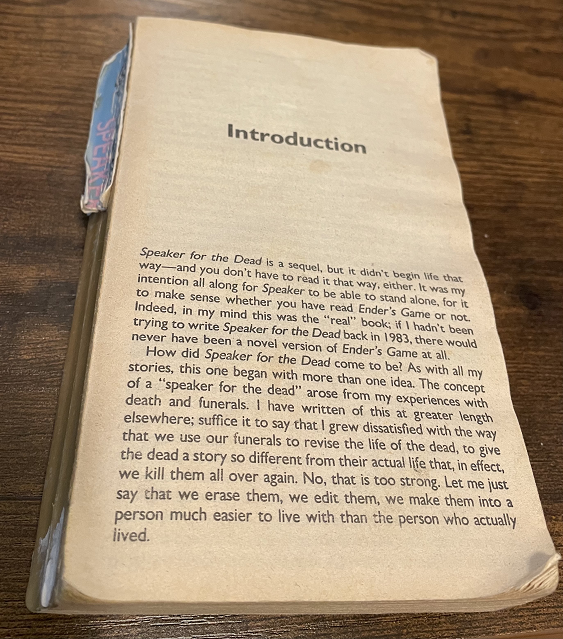

Bias on the table, this is of my all time favorite books. I maintain that it’s far better and meatier than Ender’s Game, and I’ve read my copy well over a dozen times front to back. This is it, if you’re curious:

I love it. It’s a fantastic story and I’ve yet to see any deep analysis of it beyond the basic themes of the novel or simple book reviews. This is a real shame since the book plunges in so many different directions so I figured I’d scrap together my thoughts over a series of posts.

A few editor’s notes:

- I love this series of books. If my analysis appears too Talmudic, I apologize in advance. This is the analysis I would want to read and it may dive into the esoteric minutia at times.

- I’m going to avoid summarization as much as possible. If you haven’t read the book before, you will likely be lost.

- Likewise, there will be spoilers for the entire series. I’m not going to caveat them or black-line them.

- Finally, I’m going to shy away from diving into Card’s personal politics, statements, etc. except when I can’t avoid it. I don’t know too much about them in the first place (other than that he’s a controversial figure), and I also don’t think they’ll be super relevant.

Like everything on this blog, I hope you enjoy this and find it useful.

Prologue

The prologue of this book does a fantastic job of setting the stage for what’s to come, especially on reread.

It gives the explanation behind the Brazilian culture, Portuguese language, and most of the context around Lusitania as a whole (topics we’ll get into later, I’m sure).

I have a lot of quibbles with Card’s worldbuilding. He seems to only sincerely think about it when it suits him, and in this case, he did a good job. Though I have to roll my eyes at this:

In the year 1886, they disembarked from their shuttle, crossed themselves, and named the planet Lusitania - the ancient name of Portugal.

While this is factually true I can’t help but sigh that it just so happens that this planet is also the one which triggers the first true war in the Hundred Worlds. What a coincidence!

“It is another chance God has given us.” … “We can be redeemed for the destruction of the buggers.”

This was a great way to hint at one of the central themes (that they debate much more obviously in the later chapters). A large crux of the book rests on whether or not humans can truly recognize the piggies as intelligent or if they are simply creatures to be used by humans. It comes across as a throwaway comment here, which is a nice bit of subtly. Likewise:

The piggies were not to be disturbed.

A block quote of this really doesn’t do it justice. As the final line in the prologue and disjointed from the rest of the text on the page, it’s oddly menacing and dripping with meaning.

The Hundred Worlds is a weird place to live

Card’s view on space colonization seems to be a bit like the colonization of America. Earth is overcrowded and cultures can’t live peacefully together, so each culture, religion, etc. breaks off into its own planet where it’s free to practice and do as it pleases. Not only that, but that ethnographic group also gets claiming rights on new planets it colonizes.

There’s inter-galactic democratic values like freedom of religion and expression (as we see later), but by and large the planets that we see are mono-culture blocks: Lusitania, Path, and Trondheim. Like the Pilgrims on the Mayflower, the people here seem to be escaping “society” to live the way they want to live with who they want to live with.

I dunno, it seems a little depressing that the future holds us bifrucating into our own (literal) little worlds instead of forming a multi-ethnic democratic society. I’m going to dive into this more later, but these places seem to be incubators ripe for cultural extremism and intolerance of whatever minority happens to be there. As we see later on!

I will say though, this is consistent with the world of Ender’s Game. There, Earth was collapsing due to over-enforcement of laws restricting religion, child birth, etc. so it makes logical sense that the reaction to that is a republic of cultural/religious ethnostates. This leads to a fascinating world in the novel, but it does feel like a bit of a reductive view of humanity that we can only get along when we’re a galaxy away from one another.

Or, viewed another way, perhaps this is the pinnacle of human achievement? Each person able to live freely with their plot of land, according to whatever creed they desire - the American West extended indefinitely.

Chapter 1: Pipo

A brief note on the books’ structure. Each chapter begins with an excerpt of a text from somewhere in the story.

I personally love this. It often allows a great bit of foreshadowing or tidbits into the rest of the world. I think your mileage with it will depend on how much you can tolerate not understanding the words on the page. So often, these documents throw out terms that have yet to be introduced or situations you have to simply intuit.

The first excerpt comes from Valentine’s Letter to the Framlings. The term framling has not been introduced, nor has varelse, nor raman. It’s kind of annoying and much of the language in the book does this - gives you minimal context and hopes you can piece it together.

I hated this pseudolanguage on my first read, but it’s grown on me as I’ve come back to it.

The difference between raman and varelse is not in the creature judged, but in the creature judging. When we declare an alien species to be raman, it does not mean that they have passed a threshold of moral maturity. It means that we have.

I find this to be an… odd statement from Valentine. It’s surprisingly hippie-ish. Varelse are beings which you can have no communication and yet we are supposed to view them as on the path to intelligence? Is she also a vegan? Perhaps, but then (and I’ll come back to this) in Xenocide Valentine is more or less on-board with decapitating the descolada - a true varelse being.

I understand that this is written as Demosthenses, but still, it’s so sanctimonious.

The Piggies

The piggies are fantastic. Everything about them is brilliant. First, and I can’t stress this enough, I love how they are truly alien.

They aren’t monsters or “basically human but with this one weird quirk.” No, they are alien, very alien in the most literal definition of the word. This is so much more interesting to me than typical science fiction and Card paints them as similar enough to be understood, but still very weird.

Perhaps the touch I love the most is that their body language is both logically consistent with their world and also alien!

Rooter held still in the expectant posture that Pipo thought of as their way of showing mild anxiety, or perhaps a nonverbal warning to other pequeninos to be cautious.

Rooter’s holding still like that because that’s what a tree does. Like humans, he’s reverting to what brings him childlike comfort in a stressful situation. A human plays plays with their hands; A pequenino becomes like a tree. This is great stuff and we’ll talk about it more as it arises.

The Minimal Contact Law

The only other intelligent aliens that humankind had encountered were the buggers, three thousand years ago, and at the end of it the buggers were all dead. This time Starways Congress was making sure that if humanity erred, their errors would be in the opposite direction. Minimal information, minimal contact.

I think the slow play of this works well. My first read of this is that it makes sense and is a fair and reasonable thing to do. The revelation throughout the books that this is a form of human-supremacy via fiat is clever.

Indeed, a more astute reader would pick up on the fact that non-intervention is not the opposite of destruction. The opposite of destruction is giving life and enhancing it, which this rule obviously doesn’t do as it would have allowed the piggies to suffer a massive famine (this is mentioned later).

I will say, you should never attribute to malice that which can be ascribed to ignorance. The Starways Congress becomes almost comically evil later on, but now their a relatively benign force. I don’t think (a) this rule is obviously terrible and (b) it was necessarily made with evil intent. More likely, it’s a hastily made, poor beauracratic decision that stuck around even after they realized the implications. And that’s where it becomes evil.

Pipo has certainly realized the hipocrisy and stupidity of the law, but, again, it’s the inertia to change it that’s truly wrong:

I suppose because within my area of expertise the regulations they have placed upon me make it impossible to know or understand anything. The science of xenology insists on more mysteries than Mother Church.

Ha!

A note on Xenology

More than a thousand scientists whose whole career is studying the one alien race we know, and except for what little the satellites can discover about this arboreal species, all the information my colleagues have is what Libo and I send them.

What the f** do these people do all day? They *literally cannot intervene with the piggies! Are they just sitting and churning out papers hypothesizing about the piggies? If they are, they’re terrible at it.

You would think at least one of them would have noticed the change in their hunting patterns that Jane reveals later on. Or, deduced their weird reproductive strategies. In fact, it’s later revealed that they never even ask about the xenobiology of Lusitania. Which is a massive part of anthropology!

Perhaps their disinterest is meant to signal the general corruption and malaise of the Starways Congress, but even so, I find it a little stunning.

I feel like they should have just been removed from the book. They don’t add anything, and their jobs seem completely inconsequential. It’s an instance of Card’s lazy worldbuilding throughout this novel. He needs them there for the plot to proceed, but that’s about it.

Novinha

There’s a lot to be said about Novinha and I won’t get into it all here, but her childhood is so incredibly tragic. She loses her parents when she’s ~8 and is then completely ignored by everybody around her:

It was a sad thought, that except for the Filhos, who ran the schools of Lusitania, there had been no concern for the girl except for the slender shards of attention Pipo had spared for her over the years.

I have to make a brief point about the people of Milagre as they are an essential character in this book, and yet are completely asinine in every way. I’m not sure if this meant to be a critique or not, but imagine an extremely Catholic community completely abandoning the daughter of two revered saints.

It doesn’t make a lot of sense to me, but perhaps they’re all just assuming it’s somebody else’s problem? It’s oddly cruel for such a small community, and one that’s repeatedly described as tight-knit.

Either way, I think her plot arc up till here makes sense. She’s suffered deep trauma and her withdrawl from society mirrors many children’s coping mechanisms. Her conversation with Pipo is one of my favorites in the book. Her words betray her childish nature despite the adult exterior, and Pipo masterfully draws that out of her.

Novinha and Ender are foils for one another. They have a shared trauma, and later a shared guilt. I find her turn towards the Speaking community oddly sweet. A way to give her life meaning amid a sea of misunderstanding, while also thumbing her nose at everyone around her.

Novinha is a little too self absorbed, and later a little too wrapped in guilt, but I don’t have a lot to say about this section. It makes sense and I like it as do I like her budding relationship with Libo.

Rooter’s Death

Pipo and Libo speculated that perhaps the human example of sexual equality had somehow given the male pequininos some hope of liberation.

Once again, we see the complete blindness of the Xenologers to view the piggies as raman. Rooter was actually killed because he learned something about them. They’re immediate speculation is that the piggies want to be human. Despite Novinha (accurately) pointing out that they have their own customs and way-of-being apart from humans.

Rooter’s evisceration is bloody and quite revolting. The piggies ritualistic gutting is one of the things that makes this book so good. It triggers such a disgust response in us while being a thing of great love and reverance for the piggies. Again, the piggies are alien. They aren’t little humans and they don’t necessarily want to be. The juxtaposition of their ways with ours and the inversion of them is such a neat concept.

I know other science fiction novels explore this as well, but Card does it with such humanity. Not only that, but Rooter’s death becomes the central mystery of the book - why do the piggies ritualistically slaughter one another? It’s weird and bizarre.

I think it toes the line really well of being strange, but not so strange that it’s impossible to visualize or engage with. Death is such a universal concept that it works well as a vessel for the message Card is trying to get across.

Pipo’s Death

A note about Pipo: Pipo seems like an incredibly good person. The book later attempts to paint Libo as the one more loved by the community of Milagre, but, from a narrative perspective, we see a lot more of Pipo than Libo.

Pipo, albeit too late, takes in an orphan girl, provides her with something resembling a family, and empowers her dreams. He’s incredibly sweet and thoughtful, and he’s one of the few characters not consumed with guilt and sadness over his traumatic past. It’s really quite refreshing and I wish Libo got this treatment as well.

… with Pipo a loving but ever remote Prospero. Pipo wondered: Are the pequeninos like Ariel, leading the young lovers to happness, or are they little Calibans, scarcely under control and chafing to do murder?

Pipo’s characerization is just so pure. Libo, meanwhile, is essentially absent except what you hear about him from other characters. Even then, his central plot arc is that he repeatedly cheated on his wife and left his second family to suffer at the hands of an abuser.

Plot-wise, I think this works well, but it does seem a shame. I wish Libo was more than “basically Pipo but better.” To devil’s advocate my own thoughts here, this might be better? Marcao and Libo are characterized more by the impact they have than the people they are. There’s a lesson in there somewhere…

They found him all too soon. His body was already cooling in the snow. The piggies hadn’t even planted a tree in him.

I understand the necessity of Pipo’s death to the narrative, but I do wonder how this played out in practice. We know Pipo was becoming disillusioned with the minimal contact policy already, so how did this conversation play out between him and the piggies?

Piggies: “Hi, you have shared this valuable information with us. To reward you, we will plant you or you will plant one of us.”

Pipo (internal monologue): I can’t ask them what planting is, that’s against the rules! Oh my, they have knives made of bone. What are they going to do? Oh they are pinning me down. I think I’m going to be killed. Oh no!

I dunno, I feel like Pipo would have been like “uh, what are you guys doing? And why?” Besides, the piggies are not physically that strong. There’s no signs of violence from Pipo and I think they would have stopped if Pipo literally fought back.

It just seems a little too cute that the only mention of this is that Pipo died because he couldn’t kill. I’m not sure this is true! He could have broken the policy and talked to the piggies the way Ender did. Which not only seems reasonable but would probably been allowed given that his life was in danger.

Once again, the deaths of Pipo and Libo are plot points that are just a little too convenient. Perhaps sheer terror overwhelmed them both and they went limply to their deaths? It’s not out of the realm of possibility, but the way everyone here throws up their hands seems out of character for both Pipo, Libo, and the pequeninos.

In Xenocide, Quim is killed by the piggies after he’s improsined inside a tree. This does actually make sense! The tree could overpower him and keep him there, and he submitted to it willingly.

Perhaps I’m misreading it, but when Ender kills Human at the end, there’s quite a bit of ritual involved. It’s not an immediate execution nor is Rooter’s. They are taken to the wives first, at the very least, and, at this point, I can’t help but think that either Pipo or Libo would be like, “uh, hey what’s going on here?”

They may have not believed them and simply thought their only escape was to murder another piggie, which they couldn’t do.

It’s a sweet thought, even if it stretches my credulity.

Conclusion

This is a brilliant opening to the book. I like how it starts not with Ender, but with Pipo, Libo, and Novinha. They’re plot arcs are what drive the core mysteries of the book, and it’s appropriate to start there. I imagine it was a bit of a shock to new readers to start the next Ender’s Game book and not really hear all that much about Ender.

I’ve always found the side characters in these books a bit more interesting than Ender himself, though, so it’s never bothered me.

But, on to Ender!

tags: posts - speaker for the dead analysis